The former head of the RCMP Emergency Response Team says there should have been more support available for members after the Nova Scotia mass shooting.

The Mass Casualty Commission has released a new document detailing the 13-member team’s response to the April 2020 tragedy.

They were tasked with tracking down the Portapique gunman and finding the victims.

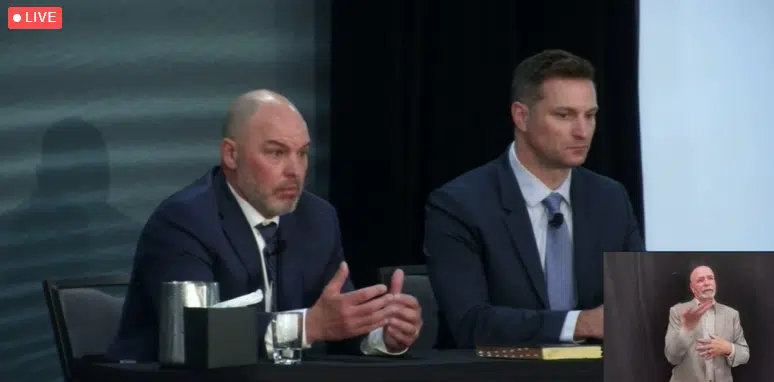

Cpl. Tim Mills served as the team lead at the time and was joined by fellow member Cpl. Trent Milton during a witness panel at the public inquiry on Monday.

Milton took over as leader when Mills decided to retire six months after the shootings. He had served 29 years with the RCMP.

When Mills spoke on Monday, he reiterated the team did the best they could, but also expressed frustration with his former employer.

“So the RCMP as an organization wants to give this impression that they care about their members,” Mills says. “Commissioner Brenda Lucki has said herself, ‘We’ll do whatever we can. We can’t do enough.’ The way we were treated after this is disgusting, absolutely disgusting. It’s the reason I left the RCMP.”

Mills says he was contacted at 10:45 p.m. on April 18th, 2020 to mobilize members to Portapique where they spent nine hours.

The Emergency Response Team is described as a group of highly trained members who responds to high-risk situations like weapons incidents, hostage-taking, and high-risk arrests and warrants.

All 13 ERT members answered the call that night.

Mills reported the team was five members short of what had been recommended and said it was difficult to navigate in the dark as they had to rely on directions coming through their radios. A tracking data app wasn’t working on their phones.

Mills also believes they should have had access to a helicopter that night to search for body heat signatures.

Mills called for trauma support after the shooting tragedy

Meantime, Mills says in the days following the tragedy senior management should have granted more resources to officers. Staff were provided initial support by a team of three psychologists.

But Mills says management turned down a request for the team to debrief at headquarters for two weeks by working on administrative duties so they could process the trauma together.

He adds the team’s eight part-time members were told to return to their front-line duties in their home detachments or take sick leave just over a week later.

“We went out and we laid our best down to stop this threat to save as many people as we could. We honestly did,” Mills says. “We went to work the very next day. Most guys were back in, writing up notes, doing tasks, debriefings … because you’ve got a bunch of resilient guys who want to work.”

He says management also told staff to speak with like-minded people, talk openly about their trauma, and stay busy to prevent PTSD and trauma.

“There are members off because of Portapqiue, not working, that are still off today, that didn’t see what we saw, didn’t experience what we experienced, we were at multiple sites, multiple casualties, and they forced our guys back to work, our part-timers back to work, a week-and-a-half after,” Mills says.

Mills adds he wanted to see an investigation into why staff weren’t given a longer break. He says that never happened.

At that point, Mills said he was done working for a “broken organization.”